A Barbary Pirate, Pier Francesco Mola 1650

The summer sun is falling soft on Carbery’s hundred isles.

The summer sun is gleaming still through Gabriel’s rough defiles…

And full of love and peace and rest – its daily labour o’er –

Upon that cosy creek there lay the town of Baltimore.

– The Sack of Baltimore (Thomas Davis 1844)

On 19th June 1631, the inhabitants of Baltimore in West Cork settled down for the evening. At that time of year, the days in Ireland are long and the sun doesn’t set until past 10PM. Perhaps, as twilight lingered, Joan Broadbrook placed a hand on her pregnant belly and smiled at her husband Stephen and their two children. Perhaps William Gunter led his seven sons in prayer before tucking them into bed.

Baltimore was a colony, a “town of English people, larger more civilly and religiously ordered than any town in this province”, according to the Lord Bishop of Cork. The Protestant settlers earned a living by catching and processing pilchards. In summer, the village likely stank of fish.

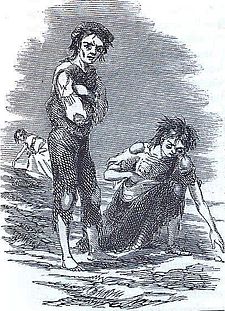

As the sun finally set, a group of ships anchored themselves at an inlet just outside Baltimore Harbour. Their leader was known as Murat Rais of Algiers, although once he had been called Jan Janszoon of Haarlem in the Netherlands. His men were Barbary Corsairs, pirates from the coast of North Africa. Murat was a renegado (the term rais simply meant “captain”), a European sailor who had converted to Islam and now waged terror on Christendom, although likely more for the sake of profit than for belief.

At two in the morning, the corsairs came ashore at The Cove of Baltimore. They ran up the pebbled beach in darkness – and then attacked.

The yell of “Allah” breaks above the prayer, and shriek, and roar,

Oh! Blessed God! The Algerine is Lord of Baltimore.

– The Sack of Baltimore (Thomas Davis 1844)

Iron bars broke down the doors, and torches lit the thatched roofs on fire. Dressed with turbans and red belts, armed with curved scimitars, the Barbary Corsairs came from many nations and yelled at the villagers in many languages. Any European who lived near a coast would have heard rumours about the vicious “Turks” from the Barbary Coast, but nothing could have prepared the people of Baltimore for the real thing.

All was confusion and terror. Stephen Broadbrook was separated from his family, as was William Gunter; although both men escaped, their wives and children were captured. John Davys and Timothy Curlew resisted and were killed. All in all, 109 people were taken prisoner: 22 men, 33 women, and 54 children. It would be the largest attack by Barbary pirates on Ireland or Great Britain.

The elderly were not valuable to the slave traders, so Old Osbourne and Alice Head were left behind on the beach.

They only found the smoking walls, with neighbour’s blood besprint

And on the strewed and trampled beach awhile they wildly went

Then dashed to sea and passed Cape Clear and saw five leagues before

The pirate galleys vanished, that ravished Baltimore.

– The Sack of Baltimore (Thomas Davis 1844)

When the ship arrived in Algiers, the traumatised captives were led ashore. The Algerians demanded ransom, but none was forthcoming. The remaining inhabitants of Baltimore didn’t have the money, and the authorities felt that paying would only encourage more attacks. William Gunter travelled to Dublin and then to London to plead for help in the return of his wife and seven boys, but he would never see them again.

So, what became of the Baltimore captives? The unluckiest men were chained to the galleys to row until they died. Other people were sold on the slave market, their teeth and limbs checked before money changed hands. Those with a trade fetched a higher price, as did children, who could be trained by their new masters. The women entered domestic service or the harem. Algiers was then part of the Ottoman Empire, and perhaps some of the Irish slaves were sent eastwards as gifts to Istanbul.

Only two of the Baltimore captives are known to have returned. After fifteen years, ransom was paid for Ellen Hawkins and Joan Broadbrook. No record exists to say what happened to the rest of Joan’s family.

Links